Did you know? Chicago Shortens Yellow Lights to Increase Traffic Ticket Revenue

Controversy is still stirring in Chicago with news that the city generated $8 million from an additional 77,000 traffic tickets, largely due to the decision to shorten traffic lights, making them fractions of a second shorter than the three-second city minimum. Although such a number seems slight, it has affected tens of thousands who have paid millions in tickets due to the city’s decision. This decrease has drawn criticism for its swift and subtle implementation, in addition to the change appearing to favor profiting over public safety.

Joseph Schofer, a professor of transportation at Northwestern University, is one of many transportation experts critical of the move. “If the machine is set to catch more people and generate more revenue, then it does not really seem to be about safety but about revenue,” he explains. The Chicago incident is reminiscent of a similar situation that occurred in Florida in 2011, when the Florida Department of Transportation reduced its policy on yellow light length.

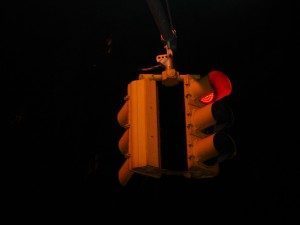

Chicago police are enforcing the new yellow light change via cameras installed at intersections, known as red light cameras. They play an essential role in charging unsuspecting drivers with $100 tickets for passing through the shortened yellow light. The cameras’ role in enforcing traffic laws are highly controversial, according to John Bowman, a spokesperson for the National Motorists Association. “I don’t think you’re ever going to get a public official on the record saying, ‘We shortened them to make more money,’” he says. “But I think that clearly goes on.”

Chicago police are enforcing the new yellow light change via cameras installed at intersections, known as red light cameras. They play an essential role in charging unsuspecting drivers with $100 tickets for passing through the shortened yellow light. The cameras’ role in enforcing traffic laws are highly controversial, according to John Bowman, a spokesperson for the National Motorists Association. “I don’t think you’re ever going to get a public official on the record saying, ‘We shortened them to make more money,’” he says. “But I think that clearly goes on.”

The first city to install red light cameras was New York City in the 1990s, with the original motivation being safety. Officials assumed that if drivers knew they were being recorded by cameras, they would be more wary of running red or yellow traffic lights. Still, as the companies that manufactured and installed these cameras continued to profit substantially from the increasing implementation of their products, the revenue-sharing model that resulted encouraged police to crack down even more on camera-detected crimes that involved passing through a red or yellow light. Police agencies were profiting alongside the camera manufacturers. This odd relationship still occurs today in places like Chicago and almost 500 other towns and cities.

Studies on whether or not red light cameras improve traffic safety are mixed. IIHS, for one, supports the camera use and claims that crashes have decreased substantially in intersections that utilize the cameras, but other research shows that the cameras increase the number of rear-end collisions because drivers may stop abruptly mid-light in fear of being caught by the camera. People for it make arguments that it prevents police bias, such as the fact that most cars who get manual tickets are red. Others say that taking the human judgement out of it is flawed, as there is a big difference between catching the end of a red light by one millisecond and blowing throw the whole thing.

This ambiguity regarding the cameras’ effectiveness, combined with the simultaneous revenue-sharing profiting by police agencies and camera manufacturers, has made red light cameras an extremely controversial topic. Some states, like New Jersey, plan to continue the use of red light cameras, while others – like Ohio – are considering banning them altogether. Nonetheless, it will be interesting to see if the public’s growing discontent with red light cameras will begin to pressure politicians to consider altering their roles and general presence.